Background

Lured by the ecological advantages of surfaces, microbial life has adapted for millions of years, resisting environmental stresses and promoting cell-to-cell communication and interactions. Most microorganisms found in our biosphere are typically found in the form of a biofilm: a tridimensional micro-ecosystem composed of aggregated cells attached to biotic or abiotic surfaces and immobilised by a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that make up more than 90% of the biofilm’s biomass.

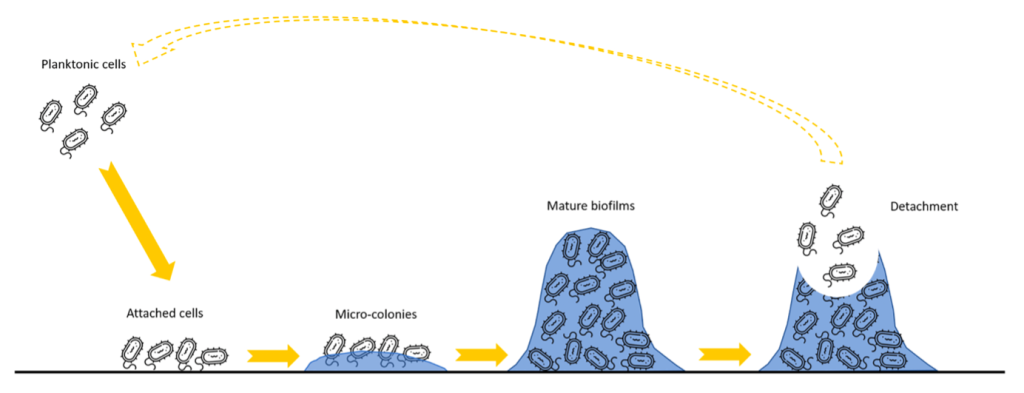

From the first surface attachment of a bacterial cell to its development into a mature biofilm, surface colonisation by bacteria can be regarded as a dynamic process. This process is typically characterised by the irreversible attachment phase of planktonic cells onto an abiotic surface and is followed by further development into microcolonies when exposed to ideal growth conditions. The final stage in the biofilm development process consists of cell accumulation leading to the formation of macrocolonies, also recognised as a mature biofilm. Biofilm detachment can occur at any stage of the biofilm formation process and may lead to the release of cells and other embedded solids or compounds back into the environment, usually in the form of environment-pathogenic bacterial cells and other embedded chemical and physical pollutants. The detachment can either be triggered by intrinsic factors, such as the natural biofilm cycle for colonising new surfaces or initiated by environmental forces, such as hydrodynamic shear conditions, physical contact, and disinfectants.

The biofilm’s EPS serves many functions for its embedded cells, such as a rich nutrient source for their continual growth and development, a protective diffusive barrier against antimicrobial exposures and provides the biofilm with its characteristic 3D architecture and other mechanical features. It is typically composed of polysaccharides and a wide variety of proteins, glycoproteins, glycolipids, and in some situations, substantial amounts of extracellular DNA. The living condition of biofilms is primarily determined by EPSs as they modulate several parameters of the biofilms, such as porosity, density, water content, charge, hydrophobicity, and mechanical stability.

The biofilm EPS’s composition and physical nature will depend on various factors, such as the biofilm developmental stage, cell physiology, the environment in which the biofilm is allowed to develop, and the microbial community structure composition embedded within the biofilm.

Once formed and established, biofilms are known to cause engineering issues such as clogging or increased resistance in piping infrastructure and even hygienic issues attributed to unwanted pathogens significant to clinical or food processing environments. Biofilms are also associated with the accumulation of absorbed chemical and pathogenic agents, thereby acting as potential reservoirs that would affect public health and food safety. In light of the well-known awareness of the concerning spread of antibiotic resistance genes in nearly all known environments, the high density of microbial contact within the biofilm’s biomass may also provide an ideal condition for guaranteeing the survival and proliferation of unwanted pathogens (including antibiotic-resistant pathogens).

The environmental Microbiomes & Biofilm Research Laboratory (eM-BRL) is, therefore, motivated by holistically describing biofilm EPS, microbial community dynamics, and the resulting biofilm properties affected by various environmental drivers and anti-bacterial strategies using a combination of molecular tools, high-throughput sequencing, analytical methods and state-of-the-art microscopy. This will be principally achieved by applying a unique experimental setup developed over the years, allowing for the study of multispecies biofilm models. Furthermore, the eM-BRL will also aim at monitoring and sampling biofilms from relevant environmental settings, whether in nature or man-made installations. Fundamental research interest will primarily focus on 1) elucidating the fundamental impacts of pollution exposure at a micro-ecological, gene expressional and metabolomic level, 2) determining the possible biofilm EPS modulation based on community shifts brought about environmental or antimicrobial stress, and how these modulations are governed by changes in biofilm EPS -composition, -structure and -architecture 3) understanding the ecology, function, survival and adaptation of targeted microbial species in their environment or from man-made processing or engineering installations.

The environmental Microbiomes & Biofilm Research Laboratory’s focus will therefore aim to narrow the knowledge gaps related to biofilm functions, properties, and dynamic processes relevant to food- and environmental- microbiology and bioprocess engineering by establishing the fundamental aspects of microbial adhesion, biofilm formation and detachment, biofilm ecology, gene expression and metabolite profiling from simplistic mono-species models to more complex multispecies biofilm models. This will be achieved through four main research axes: 1) the environmental biofilm axis, 2) the food safety research axis and 3) the bioprocess engineering axis.